Economic sanctions on Iran are no longer a temporary external shock; they have become embedded in the country’s economic structure, steadily reshaping household welfare.

Official data from the Statistical Center of Iran up to December 2025 indicate that persistently high inflation, declining real incomes and forced shifts in consumption patterns have placed Iranian living standards on a path of gradual but chronic erosion. Sanctions have emerged as a key driver of this trend, interacting closely with long-standing domestic structural weaknesses.

Inflation is the most visible expression of sanctions’ impact on welfare. Twelve-month inflation reached about 38.9% by October 2025, while point-to-point inflation exceeded 48%. For households, these figures mean paying nearly half again as much to purchase the same basket of goods and services as a year earlier. Since wage and income growth have not kept pace with rising prices, purchasing power has steadily weakened, directly translating into lower welfare.

Sanctions have played a structural role in sustaining this inflationary pressure. Restricted access to foreign exchange, higher transaction costs and difficulties in importing intermediate and capital goods have raised production costs, which are quickly passed on to consumers.

Even where domestic production has replaced imports, limited economies of scale, technology constraints and costly inputs have prevented meaningful price reductions.

Inflation, therefore, reflects not a temporary disruption but the natural outcome of an economy operating under prolonged sanctions and diminished efficiency.

Critical Channel

The foreign exchange market is a critical channel through which sanctions affect household welfare. Reduced oil export revenues and obstacles to currency repatriation have limited policymakers’ ability to manage exchange-rate volatility. As a result, the rial has become highly sensitive to political developments and external shocks, with sudden depreciations rapidly feeding into higher prices for imported goods and domestically produced items alike.

Iran’s dependence on imported production inputs means that even goods labeled as “domestic” remain vulnerable to currency shocks, helping explain why inflation has remained elevated in recent years.

Welfare deterioration is also evident on the income side. Although nominal household incomes have risen, in many income deciles these increases have lagged behind inflation, leading to a decline in real incomes. Sanctions have contributed by constraining economic growth, weakening investment and reducing firms’ capacity to generate stable, high-productivity jobs.

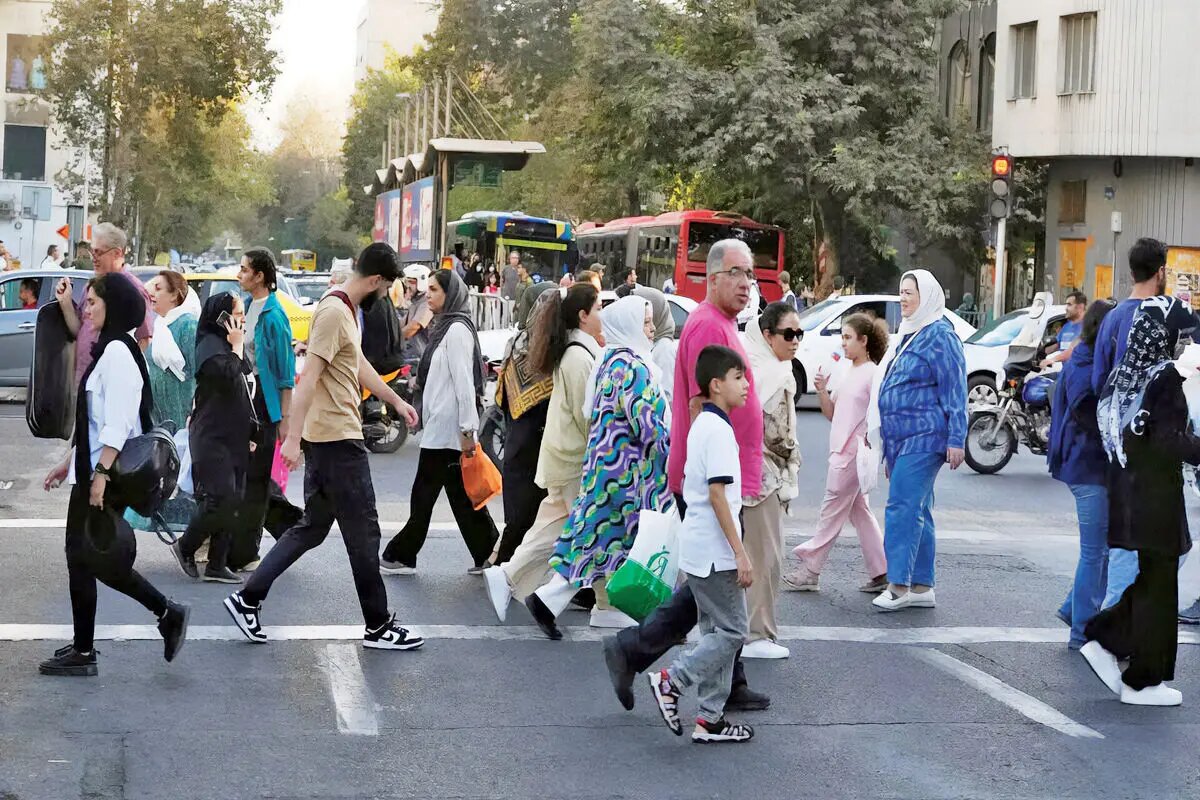

Much of recent employment growth has occurred in low-income, informal and insecure sectors, leaving households poorly equipped to absorb price shocks. This trend has been particularly damaging for the middle class, which lacks both strong asset buffers and comprehensive state support.

Another clear sign of declining welfare is the forced change in consumption patterns. The share of spending devoted to food, housing and energy has increased, while expenditures on durable goods, education, culture, recreation and even some healthcare services have fallen.

These adjustments are not voluntary but reflect shrinking real incomes. Over time, such cutbacks undermine human capital formation and deepen inequality, threatening future welfare as well as current living standards.

Government measures such as cash transfers, subsidies and price controls have provided only limited and temporary relief. Fiscal constraints and inflationary side effects have reduced their effectiveness, while structural inefficiencies have amplified the welfare costs of sanctions. Official data up to late 2025 thus depict an economy focused on survival rather than growth. Reversing this erosive trajectory will require both external de-escalation through economic diplomacy and serious domestic reforms. Without progress on both fronts, sanctions will continue to shape the daily quality of life for Iranian households.